What’s A Little Money Between Family?

We often ask clients about their best and worst money choices. It is probably not surprising to learn that “lending money to family” can show up in either column. Below, we’ll touch on the essential aspects of loaning money to family so that if you decide to go down that route (either as borrower or lender), it will be a “best” decision.

Note: for simplicity, and because it is the most frequent case, we refer to “parents” loaning money to “kids,” but these principles apply to any family or friend relationship.

Know How Loaning Money Can Impact Your Goals

The most important question to answer is, “Does this align with my goals; both financially and relationally.” On the financial front, it is an easy “opportunity cost” math problem. If I take money that could earn x%, but instead, I loan it at y% (assuming I’m paid in full and on time), will I be better or worse off? In some cases (for instance, where cash is earning low money market returns) this could actually benefit my financial picture. In other cases, it could have the opposite result.

Moreso, we encourage clients to assume the worst about the loan. Even if the loan is secured or subject to a promissory note (more on that below), how would my financial plan change if my family member doesn’t repay the loan on time or in full? Would I repossess their house or continue to require payment if their business folds? If not, then we need to factor that into the financial plan.

We also need to consider how the loan impacts relational goals. Like the “best and worst money choices” mentioned above, we’ve seen family loans help and hurt relationships. Consider the child starting a business, for instance. If mom and dad loan her money, the loan could be a tangible way of imparting a blessing on the child’s hopes and dreams. It could move the daughter to financial independence and be a story told for generations. Or it could cause everyone to walk on eggshells and make for an extremely unenjoyable Thanksgiving dinner.

Formality Is Your Friend

Be clear on whether the money is a gift or a loan. Not only is this important to both lender and borrower, but also to the IRS. Uncle Sam has clear guidelines for the tax implications of gifts, forgiven loans, and even acceptable interest rates. Be sure to inform your tax preparer of your arrangements; see article here for more details.

We’ve found that the more formal the process, the better. Drawing up a promissory note should be a minimum requirement; an attorney can draft one quickly and all parties will benefit.

If a family member balks at signing a promissory note, that could be an indication that the loan isn’t a smart decision in the first place.

We recommend defining in the promissory note whether the loan may, at the option of the lender, be renewed or forgiven. It is wise to be clear that if you make future loans, that the renewal or payoff terms might not be identical to the terms of any previous loans.

Because formality of the repayment process can also be helpful (parents don’t want late loan payments, rolled up quarters, or IOUs), consider a third-party mortgage servicer like National Family Mortgage. These services carry some additional cost, but it could be money well spent.

For slightly less formality, we will often suggest that the parent open a separate account to receive the loan payments and that all parties use a shared Google spreadsheet to keep track of payments. This way, the kid sends the checks directly to the account (not Mom and Dad), and either party can enter the amounts paid in the shared spreadsheet.

Transparency is Important

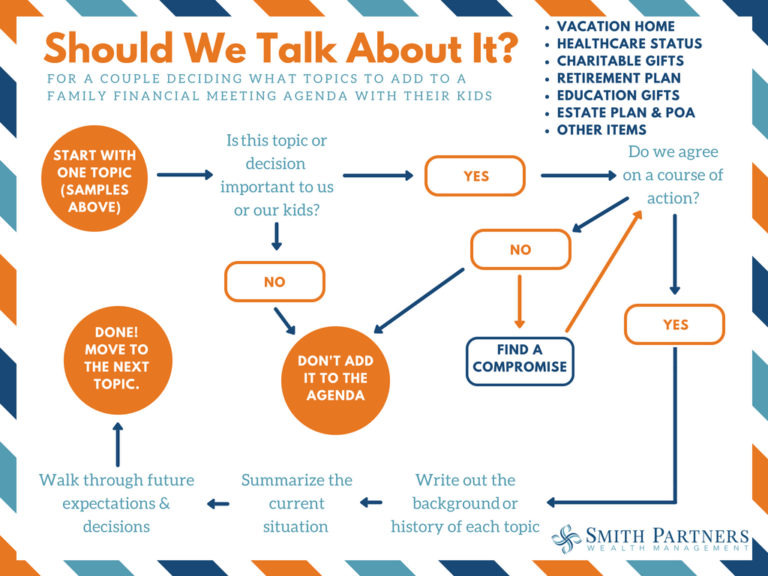

If Kid #2 is getting a loan, it could make sense that Kid #1 knows about it. That doesn’t mean Kid # 1 has to know all the details or that you have to offer loans on similar terms to all your kids. But it can be helpful to say, “I’ve made a loan to your brother; the details are with my estate planning documents.” We’ve seen hurt feelings and fractured families as a result of family members finding out about a loan after the fact (even worse, after the death of a parent.)

Attach Strings or Don’t…But Be Clear

We are comfortable with a client making a loan contingent on certain conditions; banks do it all the time. For instance, the parent might agree to loan $200k for a home purchase, but only if the home costs less than $300k. Or if the loan is funding a new business, it is perfectly reasonable to expect to see financial statements regularly.

Don’t Make Unreasonable Conditions: We don’t recommend that a parent offer to make a loan only if the kid moves the grandkids closer to the grandparents, or if the kid promises to go on the annual family vacation.

Using money to wield influence within relationships rarely turns out well.

Even if the conditions aren’t obvious, make sure to draw clear boundary lines. Set up regular times to talk about the loan, but don’t let the loan come up in every conversation.

And as hard as it could be, avoid drifting into judgment zones. “Should you be taking that vacation? You know you have a loan to pay back.” It’s unhealthy for either party to assume every interaction is a potential minefield where it’s easy to misstep on a “loan question.”

But Make One Condition: We encourage clients to make family loans conditional on their kid meeting with a financial planner. This can create much-appreciated boundary lines. Also, if the loan is the start to creating some financial independence (“giving a man a fish”), then a financial planner can help develop goals and improve money habits (“teach a man to fish”).

Family relationships are worth far more than money. Navigating the overlap between the two is challenging, but it can also be life-changing for everyone involved. Careful planning and open conversations will help to ensure sustainable success for generations to come.