Forever Stamps & The Forever Tax

In 2007, the U.S. Postal Service introduced the first Forever Stamp for 41 cents. It was a great way for the postal service to increase their cash flow, but it was also beneficial for individuals, who knew they would be sending letters in the future, to “prepay” for stamps in hopes of sidestepping future postage price hikes.

The concept of the Forever Stamp is extremely helpful in thinking about retirement contributions and tax rates. I’ll explain.

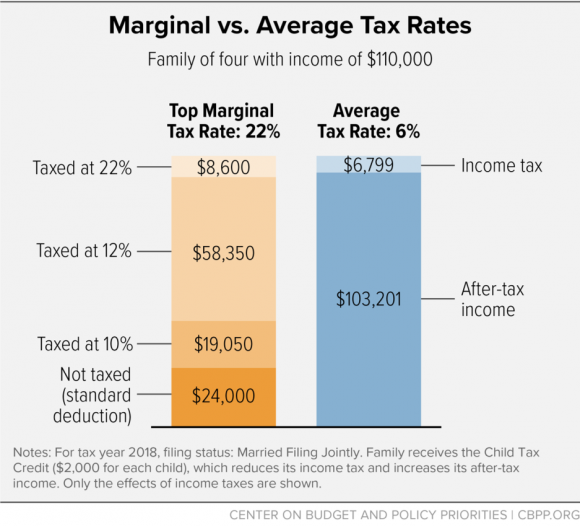

Imagine that I am married and my income is $110,000. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities points out, remember that marginal tax rates operate in layers. Simply put, for 2018, I’ll pay 0% tax on my first $24,000 of income (because of the standard deduction). Then I’ll pay 10% tax on next $19,050 of income; I’ll pay 12% tax on my next $58,350, and then 22% on my final $8,600 of income.

In this scenario, my average tax rate on the whole $110,000 is 6%, and I paid my marginal tax rate of 22% only on the last $8,600 of income.

Bonus Time

Imagine now that I have a $10,000 bonus coming my way and I’m weighing three options: I could put that money into a) my Traditional 401k, b) my Roth 401k, or c) straight to my checking account.

If I sent the dollars home to my checking account (Option C), all $10,000 of those dollars would be taxed at 22%. The IRS would get $2,200 next April, and I would keep $7,800. But what about my other options?

Buying the Forever Stamps – Roth 401k

If I put the $10,000 in my Roth 401k, I’ll have to recognize that income at my marginal tax rate of 22%, so my tax bill next April will be $2,200 higher (similar to Option C, sending the money to my checking account.)

BUT after I pay that Forever Tax I will never have to pay another dime of taxes on my $10,000 or its growth. It is the Forever Stamp of retirement savings: I’m paying a known tax rate now in hopes of avoiding a potentially higher tax rate in the future. When I reach age 65, if my $10,000 has grown to $40,000, then all of those dollars belong to me regardless of future tax rates.

Buying My Stamps Later – Traditional 401k

If I put the $10,000 in my Traditional (non-Roth) 401k, I need to remember that not all of those dollars are really mine. While I won’t have a higher tax bill next April, some portion of that $10,000 belongs to the IRS. And the portion of my 401k that effectively belongs to the IRS today is determined by my tax rates in the future when I withdraw it. I’ll be buying my stamps later, at some unknown price. It might be higher than 22%, but it also might be lower. Let’s look at two extreme examples of what happens with my $10,000 Traditional 401k contribution if tax rates are dramatically higher or lower in retirement:

The portion of my 401k that effectively belongs to the IRS today is determined by my tax rates in the future…

Rising Stamp Prices (Tax Rates) – Let’s assume that at age 65, the marginal tax rate for my withdrawals from my 401k is 50% (unlikely, but helpful for this exercise). It would be the equivalent of saying that TODAY (when I deposit my $10,000 into my 401k) $5,000 of those dollars belong to me and $5,000 of those dollars belong to the IRS. For the next 20 years, I’ll be investing my $5,000 alongside the IRS’s $5,000.

It wouldn’t have been a good idea to wait until I’m 65 to buy those “50% Stamps”. I would have been much better off happily paying my 22% tax rate to deposit it into my Roth 401k, because “22% Stamps” are cheaper than “50% Stamps.”

Falling Stamp Prices (Tax Rates) – Now let’s assume that at age 65, the marginal tax rate for my withdrawals from my 401k is only 10% (again, unlikely, but helpful to think through). This is the same as saying that TODAY, when I deposited my money in the 401k, $9,000 of those dollars belong to me and $1,000 belongs to the IRS – even though my current tax rate is 22%! What a deal.

I’ll invest my $9,000 (and keep all the growth attached to it) and I will also invest the IRS’s $1,000 (and eventually they will get their $1,000 plus all the growth that comes along with it.) It would pay off handsomely to wait to buy my “10% Stamps” in retirement.

NOTE: If I knew my marginal tax rate for the rest of my life would never change, then I should be indifferent between a Roth and a Traditional 401k on the basis of tax impact. In the event of that “tie,” the Roth option would likely be the favored option based on more favorable withdrawal/RMD/beneficiary rules and the behavioral benefit of prepaying taxes.

When Would You Kick Yourself?

Often, when we’re talking through planning scenarios, we’ll ask the highly technical rhetorical question “so when would you kick yourself?” In the case of Forever Stamps, the answer is “almost never.” The only two scenarios where someone would kick themselves for buying a boatload of Forever Stamps are a) they never end up mailing anything or b) if stamp prices decrease in the future.

Will I Mail Letters in the Future?

In the case of these 401k dollars, I will most certainly “mail letters” (withdraw money) in the future. Even if I don’t need the income, the IRS will force (or require) me to withdraw money (via Required Minimum Distributions or RMDs) and I will incur income tax on those withdrawals. And to modify a Gladiator quote, the IRS will get their money “whether it is in this world or the next” because my IRA beneficiaries have to take their own RMDs and pay taxes at their future rates.

Will Stamp Prices Go Down in the Future?

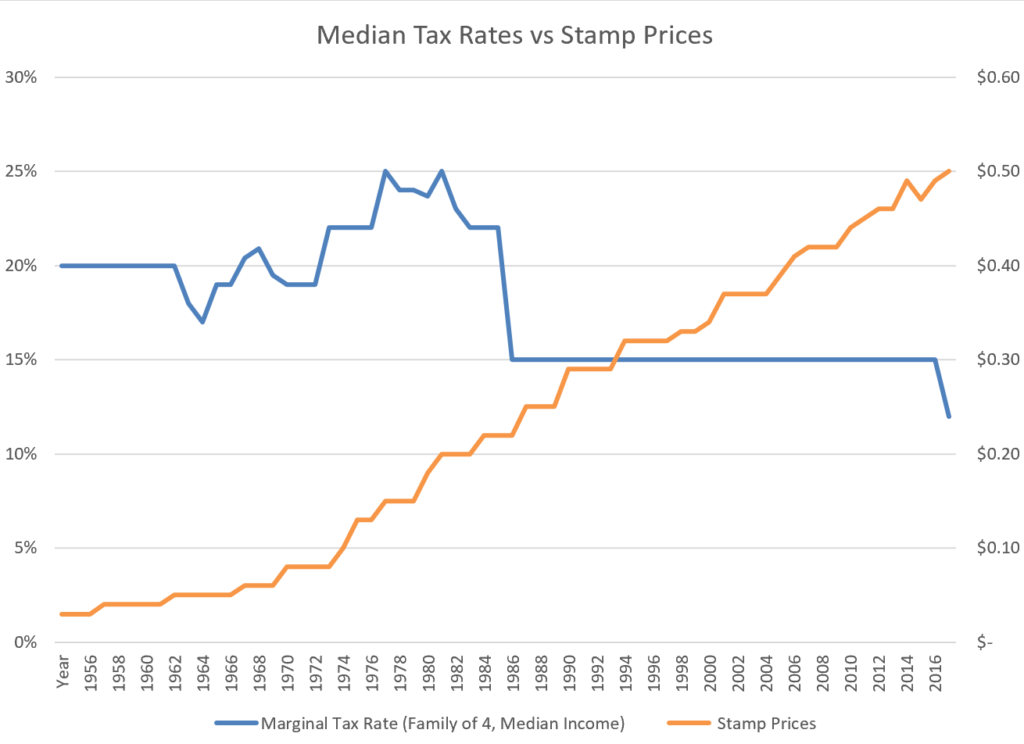

The second opportunity for kicking one’s self for buying Forever Stamps today is if stamp prices go down in the future. When Forever Stamps made their debut in 2007, it took just 9 years before the first Forever Stamp buyers kicked themselves. In that short amount of time, stamp prices had risen nearly 20% (from $0.41 to $0.49.) However, in 2016, the USPS dropped the stamp price back down to $0.47. I’m sure there were some grumpy letter-writers that day lamenting about how they overpaid 4% for all their unused $0.49 Forever Stamps. (Note: they didn’t kick themselves for long; stamp prices went back up to $0.49 the next year.)

Will My Tax Rate Go Down in the Future?

Unfortunately, tax rates aren’t as easy to forecast as stamp prices and there is much more at stake. While everyone’s situation is different, here are three scenarios to consider

Imagine a married couple, age 62, with taxable income (after deductions) of $68,000. When they earn the $10,000 bonus, they would be able to put it into a Traditional 401k and defer paying taxes until they eventually make withdrawals and pay income tax at some unknown future tax rate. If they instead put the money into their Roth 401k, they would “buy” their Forever Tax at 12%, which is a historically low tax rate. The only way they would kick themselves is if, in every year of retirement, their marginal tax rate turns out to be lower than 12%.

Likely Lower Taxes in Retirement:

Alternatively, a couple who is 62 with $395,000 of taxable income. If they put the bonus into a Roth 401k, they would buy their Forever Tax at 32%. But what if they are planning on retiring at the end of this year? Suppose next year they begin drawing a very modest income from their IRAs and Social Security such that their new marginal tax rate will drop to 12% next year. They would be much better off putting the money into a Traditional 401k and then buying their “12% Stamps” next year by taking it as a withdrawal if needed (or doing Roth Conversions if desired; more on that below.)

Unknown Taxes in Retirement, But Likely Higher Taxes in Future Working Years:

What if I have 30 more years until retirement and I am in a profession where I have good reason to expect that my income will increase meaningfully over the coming decades? In that scenario, my marginal “Forever Tax” rate today would likely be 22-24%. I could read the example above and think I should contribute to a Traditional 401k now, then wait until retirement to withdraw, paying just 12% taxes.

I would encourage someone in this scenario to consider Tax Bucket Diversification. Yes, your marginal tax rate in retirement might be lower than today…but what if it isn’t? Similar to how we encourage asset diversification (i.e. owning a mix of US stocks, Foreign stocks, and bonds) it can make sense to have some assets in retirement that I have already paid taxes on (Roth 401k/IRA) AND some assets that I have yet to pay taxes on (Traditional 401k/IRA).

So if this tax year is one of the lowest marginal tax rates I’ll see over my working years, then today is my best chance to save some Forever Tax dollars by putting money into a Roth. The downside is that I could kick myself in retirement. If I put dollars into a Roth today, I could end up like that guy who bought 1,000 Forever Stamps at $0.49 cents only to see stamp prices drop in the future. But depending on your situation, the benefit of tax diversification could make that gamble worth it. And, behaviorally speaking, having some Roth dollars in retirement can be like finding a “lost” $20 bill in your coat pocket. Yes, you’ve already paid the tax (and maybe at a higher rate than you need to) but having pre-paid the income tax can give retirees more flexibility and peace of mind.

Buying in Bulk – Roth Conversions

In the examples above, we focused on future retirement contributions. But what if someone has variable income and can’t estimate their marginal tax rate for the coming year? Or if I have some pre-tax savings but switched jobs and my new employer doesn’t offer a 401k? Or maybe I’m retired at 60 and can no longer make retirement contributions?

Through Roth Conversions, the IRS gives individuals the opportunity to take some of their dollars from a “not-yet-taxed” account like a Traditional 401k/IRA and transfer them into a Roth 401k/IRA. The result is that I pay my Forever Tax now (at my current marginal income rate) on any dollars I convert into a Roth.

Roth Conversions are a great option for someone with unknown or variable income. Because I can wait until year-end to convert IRA dollars into Roth dollars, I can wait until my tax picture becomes more clear. If in December, I see that I could recognize $15,000 more income before I cross over into the next (unfavorable) tax bracket, then I could choose to convert only $15,000 of my pre-tax IRA into a Roth IRA. I would recognize that income this year at a tax rate that is attractive to me. In other words, I only have to “buy the stamps” that I want, at the price offered to me by the IRS.

Note: I’ve spoken in generalities about tax rates and income levels, but any tax strategy needs to be thought through on a per-person basis and with all other factors of someone’s financial plan taken into account. For example, for someone who is on (or close to applying for) Medicare, recognizing additional income through Roth conversions can cause an increase in future Medicare premiums. That doesn’t mean Roth Conversions are off the table, but they need to be viewed in the complete context of someone’s financial plan.