Market Commentary Q1 – 2014

Chasing Returns and Wagon Wheels

Growing up, I loved to listen to my dad (known to me Monday through Friday 8-5 and in this commentary going forward as “Jonathan”) as he would read the stories of Uncle Remus by Joel Chandler Harris. Harris, a journalist and editor of the Atlanta Constitution in the late 1800’s, wrote down the stories he had overhead while working as an apprentice on a plantation growing up. Harris is widely credited with preserving these early African-American versions of much older African folklore and his stories subtly broke down some racial barriers present at the time. Through the words of a kind, old, fictional African-American named Uncle Remus, each chapter would take place with Uncle Remus telling stories packed with trickery and conflict (and always a life lesson thanks to Brer [Brother] Rabbit) to the young children on the plantation.

Somehow, it seems Jonathan has nearly every Uncle Remus story cataloged in his brain. Every few weeks we will be talking about something like trade deficits, earnings surprises or investor behavior and he’ll say something like, “that reminds me of the story of How Brer Dog got Tame…” This last week was no different; it was the story of Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, and the Money Mint.

The story, attached at the end of this commentary, involves Brer Fox trying to find out just how in the world Brer Rabbit’s pockets are always full of money. After dragging him along a bit, Brer Rabbit finally tells Brer Fox the secret: When he sees a wagon with large wheels in the back and smaller wheels in the front, it is quite obvious that the larger wheels will eventually catch up to the smaller wheels. Once he gets Brer Fox to believe this, Brer Rabbit declares the obvious conclusion, that money just falls out when the front and back wheels rub together: “If you know that the big wheel’s going to catch the little wheel, and that brand new money’s going to drop from between them when they grind up against one another, what are you going do then?” Not to spoil it for you, but it doesn’t end well for Brer Fox.

“Brer Rabbit says he’s sort of between ‘My gracious!’ and ‘Thank gracious!’”

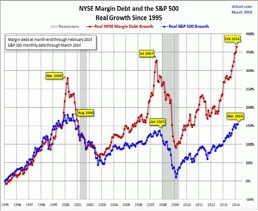

This quarter, we crossed the fifth anniversary of the bottom of the 2009 market and have been met with all-time highs, returned volatility, and money flowing into risk assets; what is frustrating to many investors is that this feels like chasing the wagon wheel. On the right is a chart from Doug Short detailing the S&P 500 Growth in blue versus the Growth in Margin Debt (investors borrowing in order to invest) in red. As you can see from the 2000 and 2007 examples, high and growing Margin Debt can be seen as a sign of investors being greedy and overconfident, jumping on a bandwagon regardless of valuation. In this extremely small sample, significant drawdowns started within 3-5 months of the Margin Debt peaks like we’re having today.

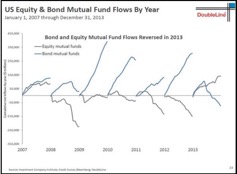

Similarly, the following chart on the next page is from DoubleLine, a fixed-income investment firm. It shows money flows into bond funds (red) and stock funds (blue), reset annually. As stocks went on a tear

The top half of the chart shows Morningstar’s Price to Fair Value graph for every stock they analyze. When it is in the red, all stocks are selling for more than Morningstar’s estimate of their worth with no Margin of Safety (back to my van, this would be like buying for more than Kelly Blue Book value). When it is into the blue, there is some Margin of Safety. Rewind the tape to 5 years ago, April 2008, and you’ll see that Morningstar (and we) thought the market overall was pretty cheap. It had just fallen from the October 2007 highs and we thought if you bought the broad market, you’d have a roughly 15% Margin of Safety going forward. A 15% discount didn’t make us overly ecstatic but we also didn’t see a reason to sound any alarms.

Over the next year from April 2008 to April 2009 we’d see the S&P 500 drop about 40%. While some fundamentals in the market had certainly changed for the worse, you can see that in April 2009 (the market’s bottom) Morningstar thought the broad market was selling for roughly 60% of fair value (or a 40% Margin of Safety). Note that this isn’t a hindsight 20/20 estimate, this was real-time. In other words, the US Equities Minivan was surely “damaged”; but even with those repairs accounted for, you could buy it at a steep discount. That was certainly something to take advantage of and we did.

Since the 3rd Quarter of 2011, we think equities have been selling for only a moderate Margin of Safety until recently when they’ve gone up into fair value territory with nearly no Margin of Safety. This doesn’t mean broad market equities can’t or won’t go up from here. For example, you can see other fair and even overvalued times (namely the beginning of 2010 and beginning of 2011) that would have created fine opportunities to make money over the following 2 and 3 year time periods…of course you would have also had to stomach 15-20% drops in the short term that came quickly after.

The difficult aspect of investing when everything is selling for far below fair value (like 2008-2009) isn’t so much in individual selections, but more in an overall willingness to stay invested despite the inevitable bad news. Broad market (index) investing and typical asset allocations work great in this environment because a “bad” decision still gets you a great return. It is like casting a net into a school of fish: you can catch plenty of fish if you have the courage to throw it out. Conversely, in a fairly valued market (like today) the difficulty is in avoiding overpriced asset classes, sectors, and stocks in favor of those that can still provide positive returns at a time of uncertainty. It is like fishing with a single hook, for a specific type of fish, knowing if you catch the wrong kind you risk losing your line.

Margin of Safety (like any kind of insurance) is cheapest and most important when everyone else thinks you don’t need it. With another run up in equities, this quarter has been an opportunity for us to scale back some of our risks, tilt even higher toward quality, and be more concentrated in our fund and individual stock selections. We don’t think it will cost us anything in potential returns; we see it as free insurance against stupidity, overconfidence, bad luck…and even a used car salesmen.