Understanding Probabilities of Success in Financial Planning

It Looks Like I’ve got a 75% Chance of Making it Home From Work

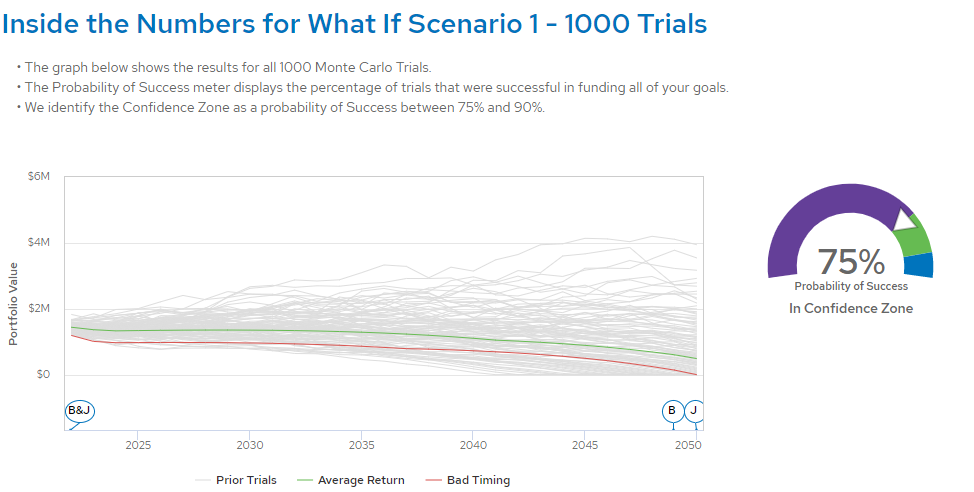

When we talk about achieving financial goals, we use the term “Probability of Success”. It comes from a Monte Carlo mathematical model that produces a number ranging from 1% to 99%. But what does a 50%, 75%, or 99% probability of success really mean?

The other week, my wife and I had tickets to see “The Lion King” at the new performing arts center in town. We knew the show would start promptly at 7:30 and, due to the cast coming down the aisles, the Purple-Vested Ushers wouldn’t let anyone in at 7:31. And really, what’s the point of seeing The Lion King if you miss Rafiki raising Young Simba high over his head.

So let’s say I had a Monte Carlo simulator that would calculate my “probability of success” for leaving work to get to the show. I punch in the variables: my projected route, my estimated time of departure, my projected driving speed, and the historical traffic patterns.

The machine then spits out my probability of success at 75%. What does that mean?

We’ll start with what it doesn’t mean. It doesn’t mean that I have a 75% chance of making it home alive, as my title suggests. If I called Millie and told her that, she would say something like, “Well that’s sad, but I know you have a couch at the office. How about you sleep there tonight and we’ll run the numbers again tomorrow?” At least I hope that’s what she’d say rather than, “75% sounds good enough, let’s risk it.”

In fact, a 75% probability of success means that if I look at 1,000 iterations of the plan, I should be “successful” in 750 of those scenarios. Meaning, I’m able to leave the office at 5:30, drive the speed limit along my preferred route, stopping by the grocery store to get some milk for tomorrow’s breakfast, and we still get in our seats 20 minutes before the Purple Vests close the doors. Success!

Unexpected Delays

- In 160 I hit all the Red Lights,

- In 80 I get stuck in a Traffic Jam, and

- In the remaining 10 scenarios I get a Flat Tire.

But in 250 (25%) of those possible timelines, I encounter some delays that require me to adjust my plan. Out of the 1,000 scenarios:

In the 160 out of 1,000 Red Light scenarios, I likely don’t need to change my route home, the time I leave the office, or the speed I drive. I’ve built in enough buffer so that I still get there 5 minutes before the show instead of my hoped-for 20. In the world of investing, time equals money. A Red Light scenario would be like experiencing slightly lower than expected investment returns. Investors can still achieve their goals, they just might not have as much buffer (assets) at the end of their lives.

In the 80 out of 1,000 Traffic Jam scenarios, I might need to make some adjustments in addition to using up my 20-minute buffer. Maybe I cut out my errand to the grocery store or drive a bit faster than I want. It’s not the path I wanted to take, but the changes I make keep my end goal intact. For an investor, a Traffic Jam might look like someone who retired at the peak of the internet bubble in 1999 or the Great Recession of 2008. Many investors had to make less-than-ideal changes to their plans for spending, work, and investments in order to make it safely home.

In the 10 out of 1,000 Flat Tire scenarios, I’m going to need all the help I can get to make it to the show on time. So I cut out the errand, weave in and out of traffic, and park illegally in a loading zone space. And even then, I might miss the first number. For investors who have planned well for retirement, the Flat Tire scenario encompasses the potential but low likelihood of starting retirement on the eve of the next Great Depression-like time period. (A note on planning for low probability events: I’ve driven for nearly 500,000 miles in my lifetime and have yet to get a flat tire (knock on wood). That doesn’t mean it can’t happen, but I plan for a flat tire by carrying a spare tire and a jack…not by leaving the office 30 minutes early each day to give me time to change a tire.

Choices to Make

So if Millie says that a 75% chance of making it to the show on time isn’t good enough, I have some choices I can make if I want to increase my probability of success.

Leave Earlier = Save More For Retirement It seems like the simplest choice would be to leave the office earlier and show up for Lion King hours before the actors. That would leave me with ample time, but canceling a half day of client meetings wouldn’t go over so well. Similarly, in planning for retirement, we can save aggressively, but we sacrifice some spending now. If that means giving up a gym membership I’ve never used – great. But if it means downsizing a house and pulling our kids from their school – that’s a “no” for me.

Drive Faster = Take On More Investment Risk Driving faster typically saves us time. But it has two potential downsides. First, it might actually get us there later or not at all. The risk of getting in a wreck or being pulled over would negate all of my speeding. The second, and more underlooked downside, is that the fast ride is stressful. Even if we speed and get to the show on time, is it worth it if my heart rate doesn’t return to normal until the cast sings “Hakuna Matata”? Investing aggressively in our early years, when time is on our side, is like driving fast at a go-kart track. There are no police to pull you over and the wrap-around bumper protects you. But investing too aggressively as we near retirement can actually decrease our chances of retiring in the confidence zone (at worst) and give us unnecessary stress (at best.)

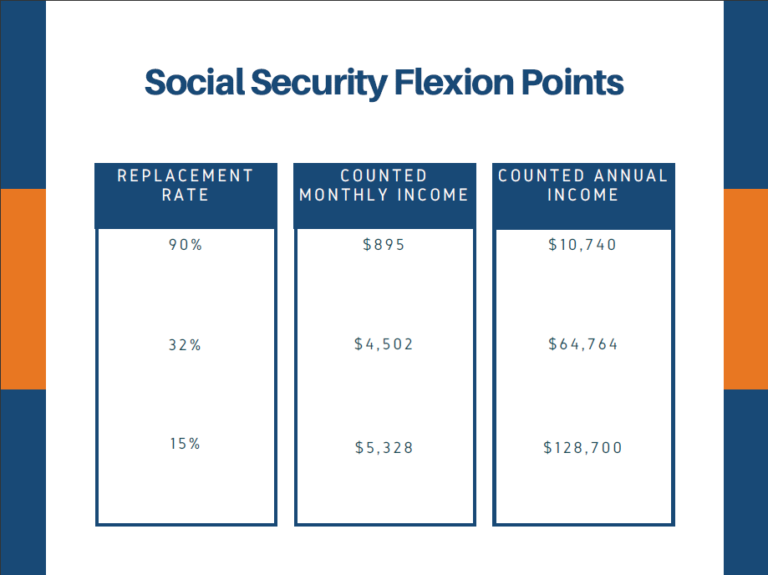

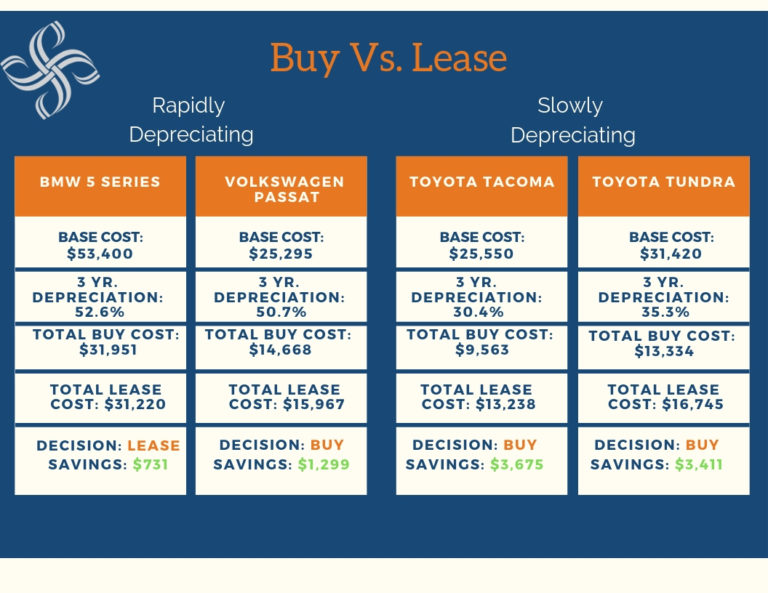

Take a Different Route = Adjust Retirement Choices When I leave work, I prefer to take the scenic route, even though my GPS advises against it. But if I wanted to increase my probability of success, I would take the quickest route and if things got desperate, I could skip the trip to the grocery store. The kids can just pour coffee creamer on their cereal! In retirement planning, this translates to adjusting some choices regarding our income and/or our expenses. As you can see below, when we change our spending choices and investment projections, we alter our probability of success.

As frustrating as it may be, there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to taking a different route. If we recommended to one client that they should cut back vacation spending by 50% they might rejoice, but for another client that could be devastating. One client would have to be dragged kicking and screaming to pick up some consulting work in their retired years, but for another it would be a dream come true. This is why it is so important to know how we spend our time and how we spend our money. And we need to take it a step further to know which of those dollars and hours that we spend are life-giving and which are life-draining (or at least unnecessary.)

The Ability to Make Choices

When I have plenty of margin for error (or “freedom to make choices”) then I can be comfortable with a lower probability of success. If I plan to leave the office in plenty of time, drive the speed limit, and shoot to arrive 20 minutes early, then I have a lot of margin for error and I’m fine with a 75% probability of success.

However, some people lack the freedom to make choices. If I am a heart surgeon, I can’t really leave work early. If I work in Brooklyn and live on Staten Island, I don’t have many alternative routes home. And if my errand on the way home is to pick up my kid from school, I probably shouldn’t skip that. In those instances, I would want to seek a higher probability of success.

In planning for retirement, we see situations where people are leaving the office a bit too late (they have undersaved for retirement.) Those who have margin to make some changes can do so. But if someone is already taking on too much risk in their portfolio, then they can’t “drive any faster.” And if someone isn’t willing to alter their income or expenses, then they can’t “take a different route.” Their only “plan” is to hope for the best.

The Value of a Plan vs. The Value of Planning

A plan is great as long as nothing changes. Let’s say I created my “Lion King Departure Plan” six months ago, but then a month after that, the city started doing road work along my projected route home. My original plan would be irrelevant and it would be wise to make some adjustments.

The same is true when thinking about our financial futures. A financial plan will include expected retirement ages, savings rates, various one-time and recurring goals, inflation and tax estimates, along with investment return assumptions. The key is to know when I should adjust my plan.

What if I have a life-altering healthcare diagnosis or a significant change to income or expenses? Yes, let’s update the plan. What if we see a dramatic shift in the tax code, long term inflation, or social security expectations? Yes, we should also factor in those changes.

But what if the S&P 500 drops by -14% at some point within the year? Should that, alone, cause me to adjust my plan? No. Because that sort of return (and far worse declines) should already be “baked” into the plan. Since 1980, the S&P 500 has appreciated at an average annual rate of +9.4%. But over the same timeline, the S&P 500 also experienced an average intra-year decline of -14%. That’s the equivalent of hitting just one Red Light on the way home. Sure it’s frustrating, but it shouldn’t be surprising.

Planning for the future isn’t a “problem-free philosophy” (as Simba, Pumba, and Timon suggest in Hakuna Matata.) It requires projections, calculations, spreadsheets, and financial models in a world of unknown and changing variables. If that wasn’t enough, a comprehensive plan also requires a careful examination of a person’s values, history, feelings, and priorities.

It isn’t surprising that, in Schwab’s 2021 Modern Wealth Survey, only 33% of Americans say they have a written financial plan. Furthermore, I would imagine that many of those plans don’t go beyond a one-time view of the numbers. But just because planning is hard or uncomfortable or requires ongoing updates doesn’t mean it isn’t a worthwhile and helpful pursuit.

We’ve found that when people engage in personalized financial planning, they tend to make it to the show on time. Not only that, they don’t have to concern themselves with how fast CNBC says they should drive or what time their neighbors are leaving for the show. They get to take the route that makes the most sense for them. Who wouldn’t want a plan like that?