The Quarter in Charts – Q1 2019

If there was ever a quarter that demonstrated the changing nature of investment markets, it was the first quarter of 2019. Below, we’ll walk through the critical themes of the quarter touching specifically on the yield curve and the possibility of a recession.

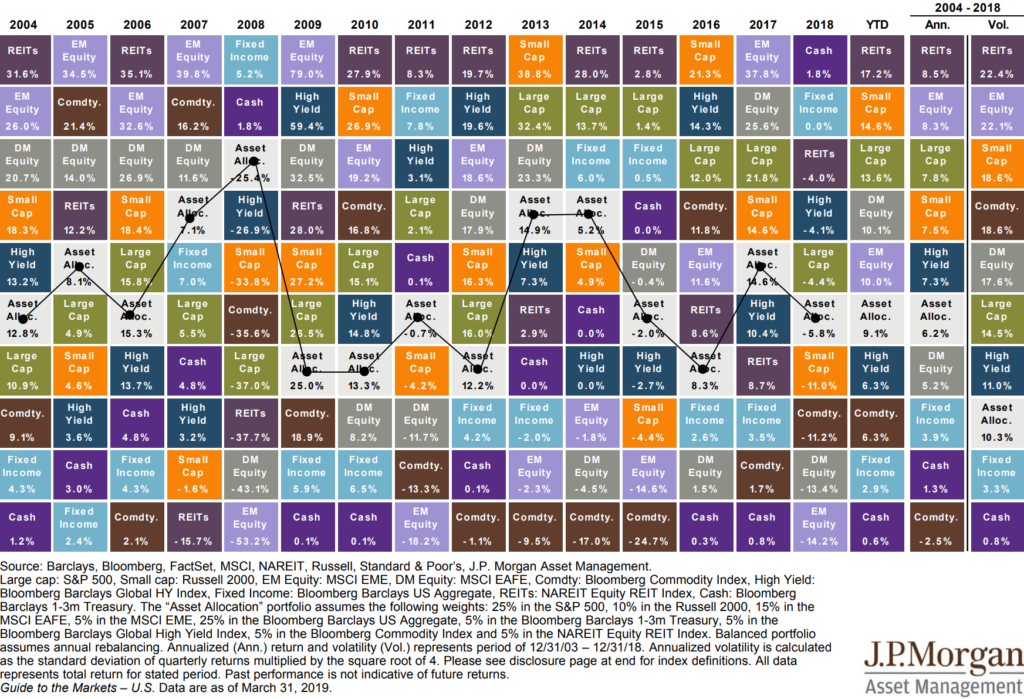

Asset Class Returns

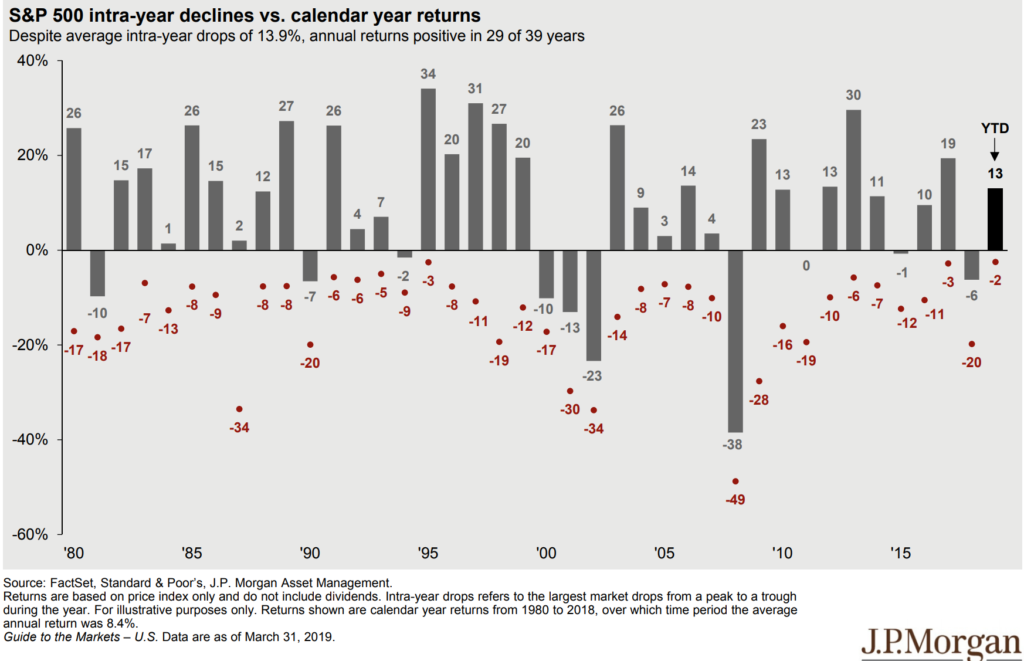

So far in 2019, investors have experienced double-digit returns in some of the historically riskier asset classes (Real Estate, Small Cap US, Large Cap US, Developed and Emerging Markets.) Contrary to 2018 when almost all asset classes had negative returns, 2019 has seen the major index returns in the positive. Also as the chart below points out, the S&P has only dipped 2% below its peak this year, experiencing little volatility.

The Yield Curve and Recessions

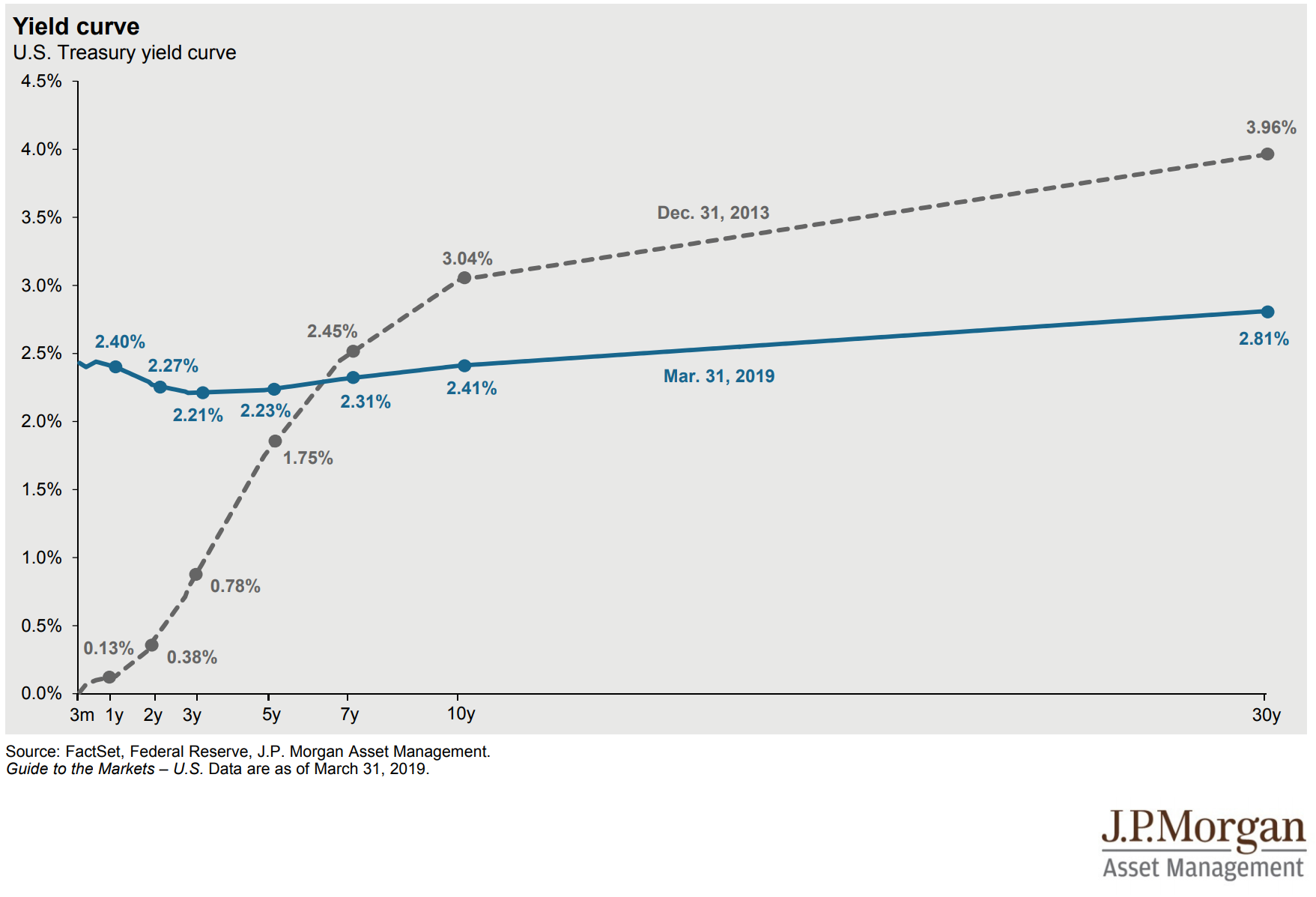

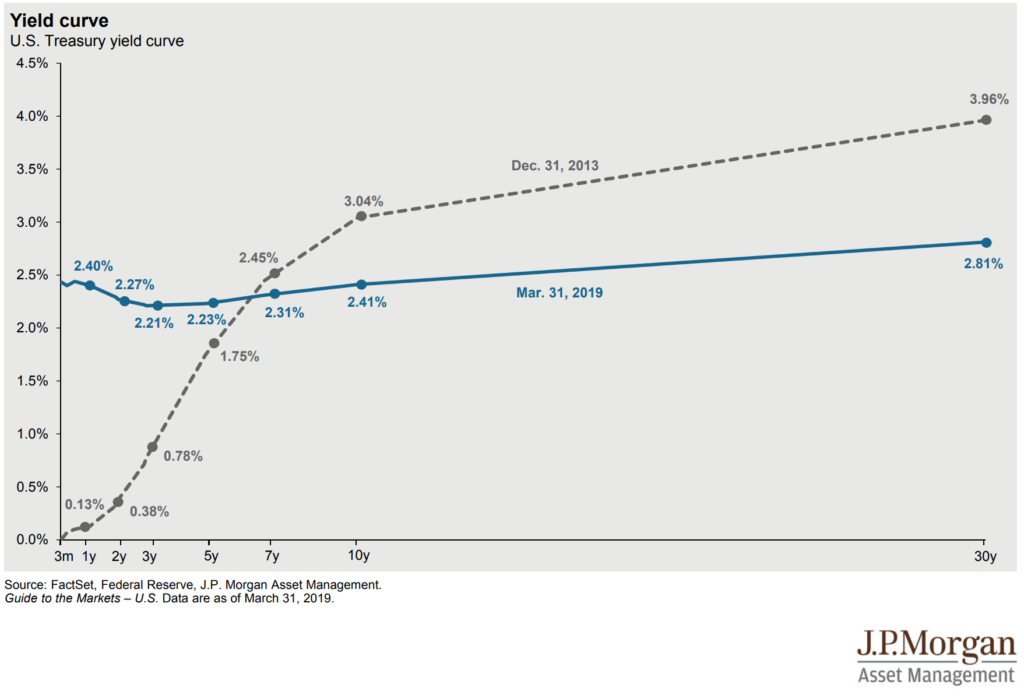

For the last 30+ years, the financial world has kept an eye on the yield curve in hopes of gaining insight into the economic future. If Google Trends search term analytics are any indication, the yield curve is occupying more attention than usual – and for a good reason.

The yield curve represents the spectrum of yields that bond buyers desire (and bond sellers demand) to buy and sell US Treasury Bonds with

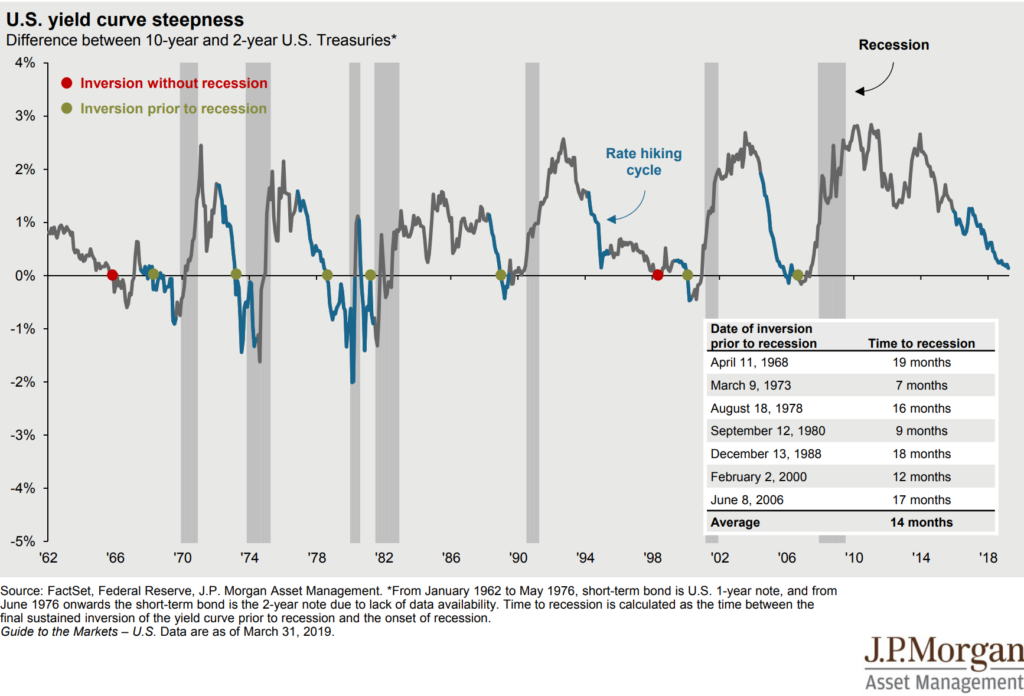

Why should we care if the yield curve is inverted? Every recession over the last six decades came 7-19 months after an inverted yield curve (green dots.) Of course, there are two other notable yield curve inversions (the red dots in 1966 and 1998) which did not result in an immediate recession. In other words, an inverted yield curve has predicted nine out of the last seven recessions (meaning, that an inverted yield curve “predicted” two recessions that never happened.)

The Yield Curve is Only Mostly Dead

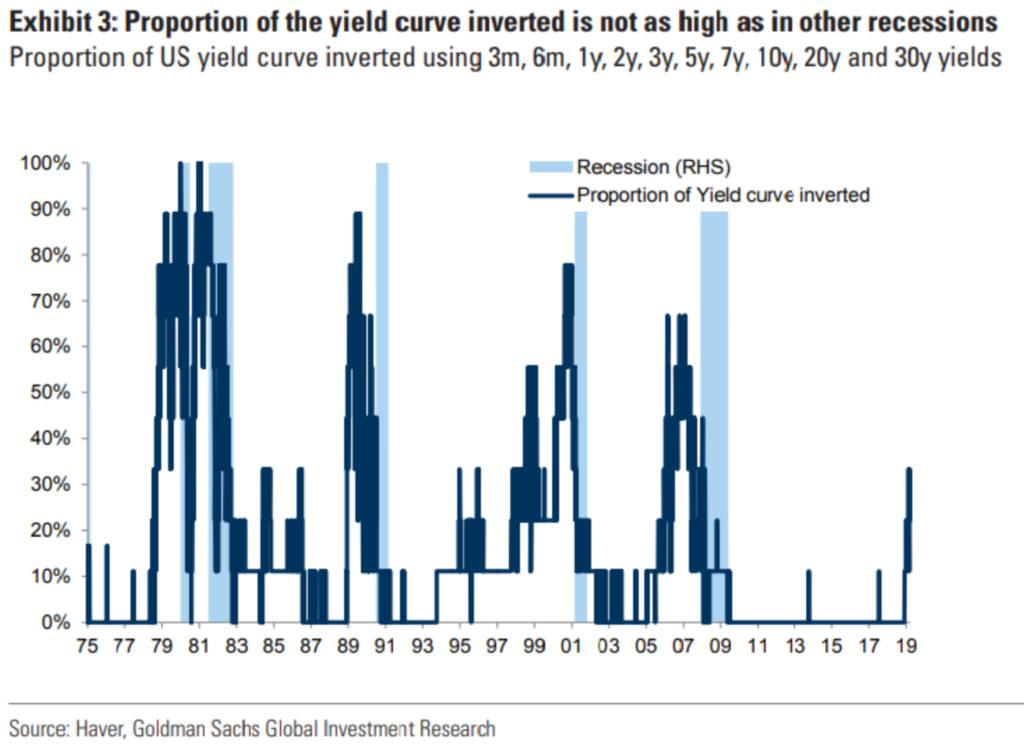

The classic analysis of the “yield curve” is the relationship between the 2-year and 10-year yield. As we see in the two charts above, this relationship (and the rest of the curve) is still mostly positive. As Goldman Sachs’ notes below, we’ve experienced prior periods with partially inverted yield curves and no ensuing recession.

However, this feels a bit like grasping for straws. It reminds me of Billy Crystal’s character, Miracle Max, from The Princess Bride. Upon hearing that the main character, Westley, is dead, Miracle Max offers some clarification:

“It just so happens that your friend here is only MOSTLY dead. There’s a big difference between mostly dead and all dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive.”

Predicting Recessions

This Spring, my 6 and 9-year-old are each playing soccer at the YMCA. For the last two weeks, they’ve had games at the same time, on fields 100 yards from each other. So my wife and I tag team back and forth, squinting to see if one of the kids is playing and trying to tell from the far-away cheers if we’re winning. We text each other “Come quick, Everett is in!” or “What was the score was when you left?” or “I think I see Finley…she’s the one in the blue camo socks, right?”

You wouldn’t think it would be difficult, but Economists have had the same luck with tracking recessions as we have with keeping up with the kids’ soccer games.

By definition, a recession marks a period of time when an economy (as measured by GDP) experiences negative growth for at least two consecutive quarters. It sounds like simple math, but because of time lags and revisions, it can be like watching a soccer game from two fields away and only getting a score update at halftime. In a 2012 article for MarketWatch, Brett Arends tried to figure out if the US was in a recession (spoiler alert: we weren’t.) He explained some history:

As for the economy: Don’t think that if we were already back in recession “someone would have told us.” It doesn’t work like that. Because of the lag-time involved in collecting the data they track, economists don’t tend to know we’re going into a recession until we are halfway back out again.

Remember the Great Recession that began in

December 2007? The economists at the National Bureau of Economic Research, who are basically the official scorekeepers of recessions, didn’t discover the recession untilDecember 2008 – a year late, and only a few months before the episode (officially) ended.Indeed I distinctly remember any number of economists, financial gurus and money managers during the first half of 2008 telling me (and every other reporter) that we were already “past the worst” and that the economy was going to pick up in the second half of the year.

The previous recession began in

March 2001 – but the NBER didn’t call it a recession until November 26 of that year. Byamazing coincidence, that was actually the month it ended (as they told us many months later).The recession that began in

July 1990 wasn’t called until April the following year. The recession that began inJuly 1981 wasn’t recognized until January of 1982. And so it goes.

Recessions and Investment Returns

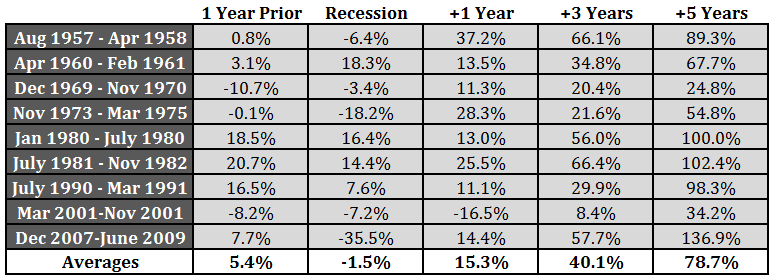

So even if we can’t determine if we are heading into a recession, the headlines tell me I should still be plenty scared of one, right? Not necessarily. I stumbled on the above MarketWatch article and quote from Ben Carlson‘s constructive blog post on Stock Performance Before, During & After Recessions. In it, Ben lays out some data for stock performance during and in the 1, 3, and 5-year periods following each recession. He concludes that for the nine recessions from 1957-2009, the average return during each recession (lasting an average of 11 months) was only -1.5%. Certainly not

Furthermore, Carlson points out that in the 1, 3 and five year periods following those recessions, the average returns were +15.3%, +40.1%, and +78.7% respectively. The cost (and the unlikelihood) of successfully timing the outs and ins of investing “around” recessions doesn’t seem like a dependable or worthwhile endeavor. The data is so fascinating that it is worth reading the blog post for yourself.

Recessions and Financial Planning

It seems difficult and potentially costly to predict the timing, duration, and impact of a recession on the life of an investment portfolio. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t plan for the inevitability of recessions in the “life” of an individual’s financial plan. We help plenty of persons whose financial plans could be negatively impacted by a recession, for instance, new retirees and those working in or owning highly cyclical (or economically sensitive) businesses.

New Retirees: Many of our clients who are in the first few years of retirement have a long time horizon in front of them. Although we use conservative estimates for investment returns, the sequence of those returns matters greatly. As Michael Kitces explains in great detail, there is a large difference between earning below average returns in the first decade of retirement versus the last decade. A wise step is to model a “bad timing” scenario into one’s financial plan. It is also useful to increase one’s cash reserves and also have a retirement cash flow plan that leaves room for reductions without compromising what is important.

Cyclical Businesses: For our business owners and those working in highly cyclical fields, “expecting a recession” might look very similar to what we would recommend for the retiree. If their business is highly sensitive to the economy, we recommend having some cash (and credit) on hand to weather and even take advantage of any recession. Similarly, business owners should have a plan in place with specific trigger points in case they start to experience a slowdown. Finally, just like we model in lower returns for our retirees, we also like to stress-test the financial plan by sketching in a lower savings rate for several years.

Because of the unavoidable but also unpredictable nature of recessions, we think it is wise to shun any financial plan, business model, or investment policy that cannot “afford” to experience a recession and the ensuing repercussions it could bring. If we cannot afford it (both emotionally and financially), then we need to make some adjustments so that we can. For more on this, please r