What Should I Do With My Next $_______?

We get this question often. A client will have just received an inheritance or sold a piece of property and has a lump sum of money. Or maybe they have just received a raise or paid off a debt and now have a higher monthly cash flow.

“What do I do with this money?” can be both the easiest and hardest question an investor has to answer. While there is no one way to address it, below we’ll walk you through six stages of our thought process (the most important being the last two.)

Recognize That Everything Has a “Return”

First, we need to establish all of the options available and the costs/benefits associated with them; or in fancy economic terms the “Opportunity Costs.” When deciding among choices A & B, Opportunity Cost shows that the decision to pick A must take into account both the cost/benefit of choosing A, but also the cost/benefit of NOT choosing B. If someone happily drops out of high school so they can make $25,000, they likely aren’t taking into the opportunity cost (missed income) of not going to college.

The same goes for deciding what to do with our dollars. Let’s say I have $3,000 and can choose to invest it, earning 7% returns (compounded for life) or spend the money on a trip. If I decide on the trip, it will cost me far more than $3,000 because I’m giving up the potential returns. Now this isn’t to say “don’t take the trip.” It might very well be worth it…we just need to know that it has an opportunity cost higher than the sticker price.

Expectations Aren’t Guarantees

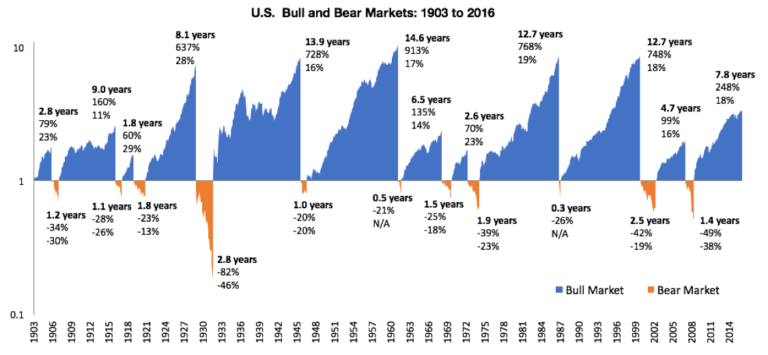

Next, we need to realize the differences between expected returns and guaranteed returns. Any seasoned investor would tell you that “7% guaranteed” is worth far more than “7% expected.” An investor’s aim should be to get the highest risk adjusted return no matter where they can find it. The two most obvious guarantees we see people miss are retirement plan matches and paying off debt.

Let’s say my company will match my first $3,000 of contributions with another $3,000. That is a guaranteed 100% return! This is likely the easiest return anyone will make in their lifetime. In my example above, if I decide to take that trip instead of contributing it to my 401k, it quickly turns into a $6,000 trip right off the bat.

Similarly, paying off debt is another guaranteed return. If I am carrying 15% credit card debt, paying it off is the same as earning a guaranteed 15% return. Warren Buffett can’t earn that on his smartest day.

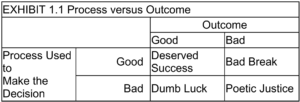

After-Tax & Liquidity Concerns

So not only do we need to factor in all possible uses for our dollars, but we need to think about the real net return and, closely tied to that, what it does to our liquidity (or access to dollars). Let’s assume I am considering paying off either my school loans or my home equity line, both at 4% interest. If I am itemizing deductions and take advantage of a interest deduction for my equity line, then my 4% rate isn’t really 4%. In reality it could be more like a 3% rate once I factor in the benefit of getting a deduction (of course that benefit decreases every year as my interest paid goes down). So in this case, paying off school debt would give us the higher “return”. Here’s a calculator to help think through this particular issue.

Closely linked is the issue of liquidity. In the scenario above, if I have paid down an equity line and then have an emergency cash need, I can simply draw on the equity line. But if I have paid down the student loan debt, the student loan company will not offer me more dollars after I have paid them down. Same goes for retirement contributions. Accessing them is possible, but comes with tax and penalty considerations. I could argue that this is a good thing; a debt or asset you can easily access could be dangerous, but either way it is a consideration.

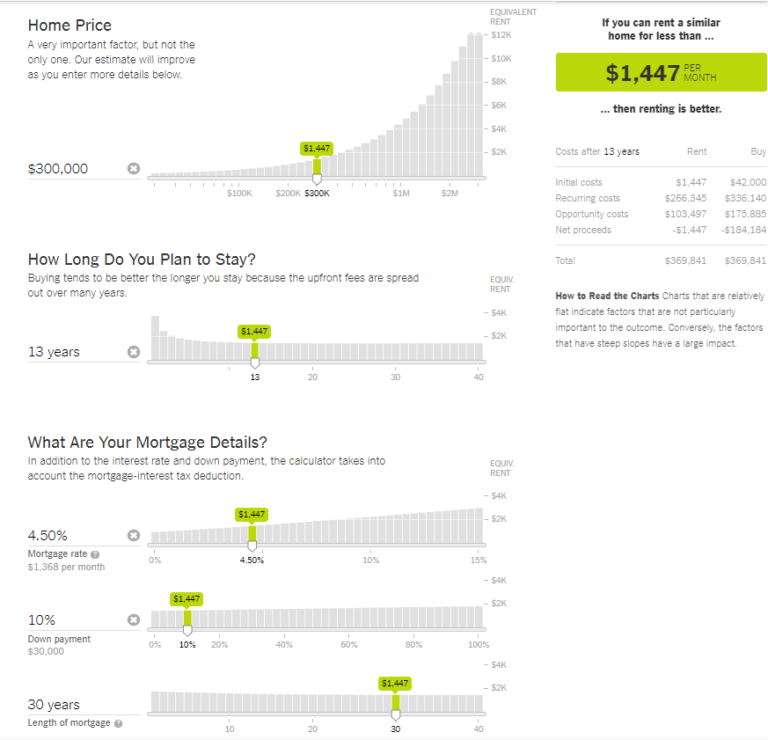

Timing Can Be Everything

At the risk of sounding like a market timer, the valuation of the market could (or at times “should”) have some consideration in the opportunity costs. As we pointed out in our post about “Why Bookies Don’t Work Local Swim Meets”, an investor’s long term returns (10 years in this case) are closely tied to the valuations (prices) at the beginning of the period. We typically only bring this into the equation at market extremes, but it’s still worth considering. An investor considering paying off 5% debt (or buying into a business or even using money to take a trip) would have a very different set of opportunity costs when making that decision at the bottom of the market in March 2009 versus making that choice today.

What Is Really Important to You?

At this point in our analysis we usually say “So if you were a computer, we would recommend…” because the math is only part of the equation. Our values, priorities, stresses, and even our own personal identities play a factor in financial decisions whether we like it or not.

Early in my career as a financial planner, we had a client couple who were spending $600 per month on dining out in addition to a large grocery bill. I’m embarrassed to say that, even though my heart was in the right place, I made them feel pretty bad about it. I asked them why they were spending so much on dining out. The answer finally came out,

“We go out to eat so much because it’s the only time our teenagers will actually sit down and talk to us.”

The look of embarrassment on my face was obvious and in a rare moment of clarity, I told them not to reduce their dining out expenses and to even consider increasing them. So what if they could retire 3 months earlier, is that worth missing a chance to connect with their kids?

The “emotional return” of a financial decision is hard to define, can change over time and might surprise us all. But just because it’s hard to quantify in a spreadsheet doesn’t mean it isn’t worth considering.

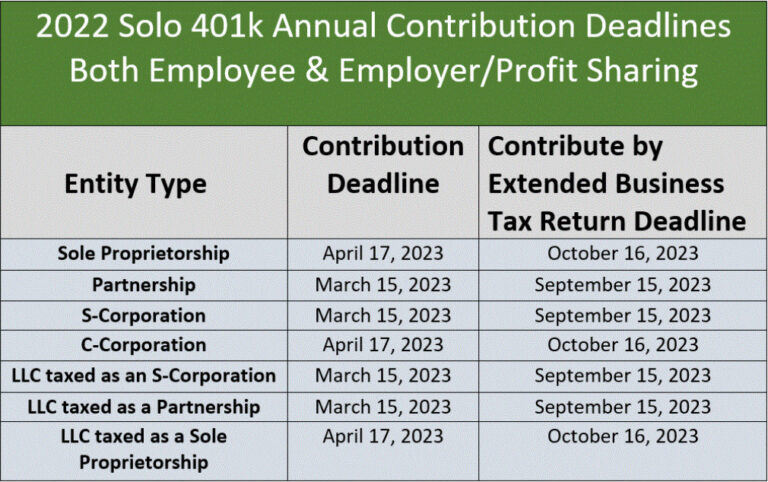

When Are We Going to Kick Ourselves?

Finally, once we have a pretty good idea about the decision to allocate dollars to a certain place (extra 401k contributions, buying a new boat, paying down a debt, giving it away) we always talk through the question of “If we make this decision, when will be kick ourselves?” It’s another way to make sure we’re comfortable with the opportunity cost.

Just today we sent money to a client to pay off a large home equity loan. We went through all of our steps above with them. Our final step was to say “Here’s where we’ll kick ourselves: if your balanced portfolio ends up outperforming the +/- 4% after-tax cost of their equity line, you’ll wish we had kept it invested.” We all shook our heads and happily took that “risk”. Every client situation is different, but in this case, they didn’t believe “kicking themselves” would hurt much: their rate was relatively high, they really disliked their debt and they have other dollars already invested in the market.

Following this process is by no means foolproof. Like some financial version of Alanis Morissette’s “Ironic”, someone might pay off all of their school debt just to have congress decide to forgive all student loans. Or someone might use an inheritance to increase their emergency fund just before the start of a Bull Market. But as we mentioned in our last commentary, a good process for deciding what to do with our dollars is far more important to investor success than a few good outcomes that were the product of a bad process.